“Despite its inescapable past, Bosnia-Herzegovina writes new chapter” (Wilson, J., 2014); “The country has been through a lot of tough times, there’s no secret about that, but this is the first major tournament for myself, and for Bosnia, it’s all new and it’s going to be great” (interview with Asmir Begović, Bosnian goalkeeper: Wilson, P., 2014). These were just some of the comments expressing excitement about the debut qualification of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) to the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil. However, their meaning extends beyond a normal pre-World Cup craziness; the World Cup bears a much bigger potential for the young country, torn by the 1992‒1995 conflict and struggling with inter-ethnic divisions, terrible economic and social situation and stagnated accession process towards the EU membership. Although to be able to answer the question “What is the social meaning of the 2014 FIFA World Cup for BiH?” the World Cup needs to start first, I will try to make some conclusions before the games actually begin. And no doubt, there will be some more posts about Bosnia since this is my dissertation topic, yay 🙂

Role of football in Bosnian society

Sport, particularly football as a favourite sport of the constituent nations, plays an ambiguous role in Bosnian society. In Yugoslavia, sport was an important tool for reinforcing the state and strengthening the multi-ethnic Yugoslav identity. Towards the end of 1980s, football underwent a strong politicisation and was used by nationalists for personal enrichment, construction of power at local level and political self-legitimisation. When the war started, each ethno-national group organised its own separate football federation and football league. The Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats identified with Serbian and Croatian national teams respectively, and not with BiH representative team, which was controlled politically by the nationalist Bosniak party SDA (Sterchele, 2007; Gasser and Levinsen, 2010). Under strong pressure and conditionality of FIFA and UEFA, Croatian and Bosniak federations merged in 2000, and the Football Federation of Republika Srpska joined them in 2002, when one united Football Federation of BiH (Nogometni/Fudbalski savez Bosne I Hercegovine – NFSBiH)[1] was established. One common Premier league was established, although the lower divisions remain ethnically separated at the entity and cantonal levels. The structure of the federation was based on a tripartite presidency and a seats-rotation system between the representatives of each ethno-national sub-federation, following the Dayton political structure. Such governance model was considered non-democratic and inefficient by UEFA and FIFA, which suspended NFSBiH from their membership and all Bosnian teams from international competition in April 2011. NFSBiH was replaced by a normalisation committee that dismissed the past officials and amended the statue by replacing the tripartite-rotational structure with a single-member presidency, based on competence instead of ethnicity (Sterchele, 2013; NFSBiH 2014). “While political institutions have remained wedded firmly to the post-war principles of division, rendering much of the state apparatus unworkable, the Bosnian Football Association has demonstrated that even the most entrenched of bureaucracies can make progress” (Kinder 2013, 161).

The world of football has lead towards partial integration of all Bosnians in a single sports community (Sterchele, 2007). The unified Bosnian Premier league has increased travelling of football fans to away matches in ethnically different towns and there have been a lot of renewed encounters of people, who had known each other before, but were separated by the conflict (Sterchele, 2010). Furthermore, “Telecom Premier League of BiH has long ago, but particularly this year, showed that football in Bosnia and Herzegovina has overcome national and entity divisions” showed a survey by the Bosnian press agency Patria (Sport.ba 2014). Namely, in the majority of the Bosnian clubs, the players come from all ethnic backgrounds and are selected on the basis of their performance rather than ethnicity, which was not always the case. As well, the Bosnian national team has become more multi-ethnic over the last decade and an increasing number of Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats support it (Kinder, 2013). On the other hand, a lot of football matches in the Premier League, but mainly in the lower divisions, are still characterised by riots, violence and slogans and offences based on the use of war symbolisms. Serbs fans are called ‘četnik’ by the Croat and Bosniak opponents, while Croats are called ‘ustaš’ and Bosniak are insulted with the word ‘balija’.[2] Although national and war symbolisms are used also by Bosniaks against Bosniaks, Serbs against Serbs or Croats against Croats and are therefore used not only to express somebody’s ethnic belonging, but rather to provoke football opponents as much as possible, it seems that the memory of the war is far from gone (Sterchele, 2010). According to Azinović et al (2012), football hooliganism is one of the main factors for fuelling nationalism and inter-ethnic violence, especially because football clubs are used instrumentally by political elites and young people are easily mobilised for violence and riots as a form of their collective expression of dissatisfaction (juvenile delinquency is very high as a result of lack of opportunities, failing education system and ineffective political and economic reforms).

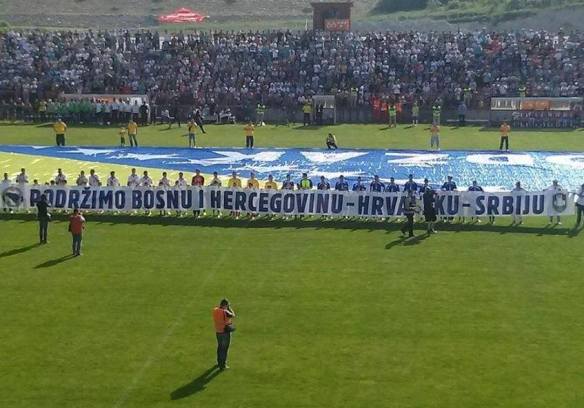

However, the recent qualification to the FIFA World Cup has witnessed people from different ethnic backgrounds coming and celebrating together. Bosnian national team, the country’s first truly multi-ethnic organisation, inspired by starts such as Edin Džeko and Asmir Begović (ethnic Bosniak), Zvjezdan Misimović (ethnic Serb) and Boris Pandža (ethnic Croat) sends a strong message of unity and cooperation and presents a source of national pride. While BiH “is at a standstill in the European integration process while other countries in the region are moving aheadˮ (European Commission 2013, 1), its emergence as a footballing nation and its participation at the 2014 World Cup have significantly increased its presence on international stage. What is therefore the social role of the World Cup for such a complex society that seems to be on the margin of international affairs?

However, the recent qualification to the FIFA World Cup has witnessed people from different ethnic backgrounds coming and celebrating together. Bosnian national team, the country’s first truly multi-ethnic organisation, inspired by starts such as Edin Džeko and Asmir Begović (ethnic Bosniak), Zvjezdan Misimović (ethnic Serb) and Boris Pandža (ethnic Croat) sends a strong message of unity and cooperation and presents a source of national pride. While BiH “is at a standstill in the European integration process while other countries in the region are moving aheadˮ (European Commission 2013, 1), its emergence as a footballing nation and its participation at the 2014 World Cup have significantly increased its presence on international stage. What is therefore the social role of the World Cup for such a complex society that seems to be on the margin of international affairs?

The FIFA World Cup, national identity and international recognition

Although the membership in the United Nations (UN) is de facto recognition of state’s sovereignty and its independent existence in the international community, being admitted to FIFA (or comparably, to the IOC) is a clear signal that a country has been accepted as a nation state by the international community. Despite FIFA’s claim that granting the membership to a national football association is guided by decisions already taken by the UN, BiH and Palestine for example were given provisional membership of FIFA before their status as sovereign nation states had been recognised by the UN General Assembly (Sugden and Tomlinson, 1998), and The Faroe Islands (Denmark) and Bermuda (England) compete independently although they exist under the umbrella of their parent sovereign states (Wiztig, 2006). Becoming a member of FIFA, “the United Nations of Football”, which has more members than the UN itself (FIFA, 2014b), becomes a medium for newly independent states and/or small and resurgent nations to register their presence in the international arena both on and off the football pitch (Sugden and Tomlinson, 1998; Tomlinson and Young, 2006).

Furthermore, the FIFA membership is important because it gives the national teams the right to play international matches and to take part in international competitions. International football is a part of the process through which modern nation-states have been made and proclaimed. ‘Our team’ at an international match intrudes in our daily routine, reminding us of with whom we stand with regard to our fellow nationals (Sugden and Tomlinson, 1998). Sport is a carrier of identity (identities) because it draws on emotions of a person. It is an important platform for expressing collective identity, which is on one hand inclusive for the members of a certain imagined community (Anderson, 1983), yet exclusive because it creates a high degree of social stratification, national and ethnic divide and therefore cross-community conflict. Especially differing and contrasting views on what constitutes a nation and/or a state make the role of sport in inter-community relations and nation-building even more problematic (Nieman et al, 2011; Sugden, 2010). This is quite the case in BiH, where the Bosnian Serbs and the Bosnian Croats prefer to identify with their respective countries of ethnic origin more than with the Bosnian state. However, according to the FIFA Statute,[3] only one association is allowed to be recognised in each country, meaning there is only one association (NFSBiH) presenting BiH in global football.[4] Such a unified representation of BiH internationally widens the imagined community of all Bosnians, regardless of their ethnicity ‒ The FIFA World Cup namely generates a number of occasions “when nations are embodied in something manifestly real and visible” (Smith and Porter, 2004, p.1). National identification and unification are stronger when the imagined community (Anderson, 1983) participates at an important and internationally broadcasted international event. Such a unified representation of BiH at the World Cup will be enhanced due to the multi-ethnic composition of the national team, which has become one of the greatest promoters of BiH in the world (Šarčević, 2013).

The role of global media in imaging the nation

FIFA World Cup is one of the most dramatic and high profile spectacles in global sports and therefore a platform for national pride and prestige. It is also one of the major global media events, producing discourses of identity and globalisation and transmitting information and representations about the participating states to billions of people (Tomlinson and Young, 2006; Horne and Manzenreiter, 2006). Huge media coverage of the World Cup therefore has the power to change foreign perceptions about a state, improve its image by emphasising its good sports performance and therefore help the country reposition itself in the international community (Lincoln and Monnington, 2002). In the case of BiH, international media seems to be keen in portraying BiH as a country that has risen from the ashes and is leaving its past behind; its players are represented as “the children of the war” who are now Bosnia’s golden generation, “uniting a once bitterly divided nation” (Beanland, 2013):

“/…/ for the first time in 20 years, this victory and this team brought together a nation torn apart by economic turmoil and political and national differences for so long. These young men showed that a united Bosnia can stand tall and proud and take its place as an equal among equals at the world stage” (Cubicle No More, 2013).

“Once I stood in soccer field-turned-graveyard in Sarajevo. Now free Bosnia qualifies for World Cup for the first time. Congratulations!” (a comment by the CNN reporter Christiane Amanpour, who used to report on the war in BiH, on Al Jazeera: Fadilpasić, 2013).

Especially the debut participation at the FIFA World Cup, with the help of global media, therefore a) increases a state’s visibility in international affairs and b) changes foreign public’s perceptions and its international reputation. This is especially important for small or less powerful states that don’t appear in the world news headlines often. An example is Croatia, which “arrived for their maiden shot at the FIFA World Cup in 1998 as virtual unknowns” (FIFA, 2014c), just seven years after its declaration of independence, and registered its international presence through securing the third place in the tournament. A small, post-war country from the Balkans therefore became a world football-superpower in the eyes of the international public. Emerging and small states are much more excited when they make the international news and often cite the international media in their own national or local news report – being mentioned in internationally renowned media becomes news in itself. Slavica Pecikoza, the spokesperson at the NFSBiH, confirmed an increasing interest of international media in the Bosnian national team: “For the preparations of our team in Sarajevo between 15 and 27 May, 92 journalists, cameramen and photo-reporters from all around the world have been accredited. We don’t even count anymore, how many there are. We have a lot of work, but we are all proud that BiH is in the media centre of the world attention, and this time for beautiful things” (Al Jazeera Balkans, 2014). Being in the centre of the global attention therefore represents a source of national pride and self-confidence, which Bosnians lack otherwise.

While foreign media keeps portraying Bosnia’s participation at the World Cup as a source of the national unification, the analysis of national and local media shows a bit contrasting and more complex results. While international media claimed that the massive celebrations across BiH on 15 October, when BiH defeated Lithuania and qualified for the World Cup in Brazil, were attended by all three ethnic groups, some of the comments on local news websites negated such perception. Bosnian Serb official television RTRS did not even broadcast the match between BiH and Lithuania, choosing to show Serbia’s qualifier with Macedonia instead (SuperSport 2013). “In Republika Srpska, the victory was accompanied with a mood that was ‘colder than cold’” (Slanjakić 2013). I have done some media analysis to understand a) how media maintains or tries to change inter-ethnic relations; b) to see the readers’ comments and try to get some basic insight into how ‘normal’ people from different ethnic backgrounds see Bosnia’s participation at the World Cup. I will not share all of it here (I need to save it for my diss), but to sum up the findings I would say that there is still a lot of nationalism and inter-ethnic hatred. Bosniak Serbs’ and Bosniak Croats’ media has been reporting on the Bosnian team relatively neutrally, and not much differently from reporting on other teams. Reactions by the readers have been more diverse. Some Bosnian Serbs or Bosnian Croats claim their support for Serbian team (which is not at the World Cup so some of them feel they will have no team to support) or Croatian team. On the other hand, there are also many Bosnian Croats and Bosnian Serbs congratulating BiH and even encouraging their friends to stop enhancing the old divisions. While the Bosnian team seems to be a great source of pride for Bosnians, the majority of Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats see Serbian and Croatian national teams as their primary teams and source for expression of their ethno-national identity.

Double role of the World Cup for BiH that might not last too long

Drawing from the theoretical approach to the World Cup and from the media analysis, it looks like that the World Cup has two main social meanings for BiH: potential to be a tool for national/inter-ethnic reconciliation and identity/nation building; and a source for increasing the presence of BiH in the international community.

Firstly, it would be naïve to say that the World Cup will bring a complete reconciliation. The analysis of domestic media has shown that some Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats are still very hostile towards the Bosnian national team. However, keeping in mind the state of Bosnian football some ten years ago, when football was completely divided along the ethno-national lines, multi-ethnic team and the fact that many Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats do support the ‘Dragons’ are a success in themselves. “More Serbs and Croats support our national team. /…/ Now it’s a natural thing that Serbs and Croats from Bosnia play for Bosnia. Things are better than they were before,” said NFSBiH’s spokesperson, Slavica Pecikoza (Beanland, 2013). The World Cup might therefore contribute to nation- and identity-building, since “it is much easier to imagine the nation and confirm national identity, when 11 players are representing the nation in a match against another nation” (Hobshawm, 1992, p.143). All three constituent nations are more likely to identify or at least support the national team since it includes players from all the ethnic backgrounds:

“The fact is that on the football pitch a pass does not discriminate between a Muslim and an Orthodox Christian. Miralem Pjanic (an ethnic Bosniak) will not refuse a pass from Miroslav Stevanovic (an ethnic Serb) because of events that took place while they were children and were far beyond their control. It is the trust that the goalkeeper Asmir Begovic (an ethnic Bosniak raised in Canada) has in defenders Emir Spahic (an ethnic Bosniak born in Croatia), Boris Pandza (an ethnic Croat) /…/” (Dedović 2013).

In terms of identity/nation building in BiH, it is important to understand Smith’s (1998) argument that nations are founded on ethnic communities of groups. Ethnic symbols provide a source which distinguishes ‘us’ from ‘them’ – and this symbols are still very persistent in BiH. Thus certain states, such as BiH, must draw on a diverse selection of cultural resources to construct cultural common denominators – such cultural elements must be credible and speak to common sense (Edensor, 2002). Edensor furthermore adopts Billig’s (1995) concept of banal nationalism, which claims that national identity is grounded in the everyday, mundane details of social interaction, habits and practical knowledge. Football as a favourite sport of the three ethnic groups, and the World Cup as ‘opium of the masses’ can therefore serve as common cultural denominators. However, national identity is facilitated also by the state’s legislative framework, which delimits and regulates the practices in which people can partake (Edensor, 2002) – as a consequence of the Dayton model, the legislative, political and educational framework in BiH unfortunately presents an obstacle rather the facilitator for reconciliation and identity building. In BiH, structural and institutional divisions are too strong to be simply overshadowed by football.

Secondly, the media coverage of the World Cup and pre-World Cup events already seems to be contributing to the increased presence of BiH in international news – and this time not because of the war, but because of their success. While this is important for Bosnia’s image abroad and for its repositioning in the international community, it is relatively different from the reality. It could be argued that the global media is portraying the unifying power of the World Cup in order to legitimise the World Cup by presenting it as a source of the good (especially when the World Cup in Brazil is at the same time target of many critics and is gradually losing its legitimacy in the eyes of global public) – stories about poor Bosnia that has risen to be a world footballing power that will bring together the divided population make much better headlines than protests in Brazil. Regardless of such concerns and of the fact that the World Cup doesn’t offer a solution to all national problems, such reporting provides an opportunity for the collective expression of pride and harmony rather than difference and might facilitate reconciliation (Van Koningsbruggen, 1997).

Similarly as in the case of South Africa, where it wasn’t clear whether the 1995 Rugby World Cup would be transformative or would only create a temporary diversion from domestic problems (Nauright, 2010), it is questionable what the long-term effect of the World Cup will be for BiH. BiH has been currently experiencing the most terrible floods in its history and although it is sad, the tragedy has brought the people together – both ordinary people, who help each other regardless of their ethnicity or religion, and athletes from Bosnia, Serbia and Croatia (Džeko, Đoković, even Ibrahimović from Sweden) and all Bosnian football clubs, which is quite a precedent in Bosnian history. Džeko wrote on his Facebook profile:

“I have mixed feelings because I believed that our participation at the World Cup would unite us, but unfortunately, we have been united by the tragedy. Hundreds of people are helping – humanitarian organisations, sports organisations, companies, individuals, and this only shows that we always have to stick together, not just in a disaster, but also in happiness and joy”.

The World Cup has a potential to bring the people together even further and accelerate “bridge-building that still eludes peace-makers and politicians” (Kinder 2013, 154). On the other hand, the potential effect of the World Cup on unity and reconciliation will probably be severely undermined by the national election in October, which will reproduce old nationalistic discourses. As well, the World Cup lasts only for a month while other factors of inter-ethnic relations (such as divided school system, nationalistic media, Dayton political system etc) will continue to exist. I cannot make any firm conclusions since the World Cup is yet to happen. The World Cup (as the opium of the masses) has the potential to temporarily heal some of the old wounds, bring the people together and present BiH in a positive way. However, it shouldn’t be an illusion about unified Bosnian society – the reality is still far from reconciled Bosnia.

[1] Its official name includes both Croat and Serb words for football (nogomet and fudbal) in order to avoid disputes.

[2]Četniks were the Serbian royalist paramilitary combatants during the World War II and the ustaši belonged to Croatian fascist anti-Yugoslav movement. Both names are used as derogatory terms. The word balija used to describe descendants of Turks of Ottoman Empire in the Balkans and has become an insult for Bosniaks, used by Croats or Serbs (Sterchele, 2010).

[3] FIFA. 2013. FIFA Statues, July 2013 Edition. Chapter II, Section 10: Admission, Paragraph 1, p.19.

[4]Although the football association of Republika Srpska wanted to play international matches, it was never recognised by FIFA and therefore the football team of Republika Srpska cannot represent Republika Srpska internationally.

References:

Al Jazeera Balkans. (2014) Veliki medijski interes za bh. ‘Zmajeve’, 14 May. Available: http://balkans.aljazeera.net/vijesti/veliki-medijski-interes-za-bh-zmajeve (Accessed 18 May 2014).

Anderson, B. (1983) Imagined Communities, London: Verso.

Azinović, V., Bassuener, K. and Weber, B. (2012) Procjena potenciala za obnovu etničkog nasilja u Bosni I Hercegovini: Analiza sigurnostnih rizika (Assesing the potential for renewed ethnic violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A security threat assessment) [online], Sarajevo: Faculty of Political Sciences, University of Sarajevo, and Atlantic Initiative. Available: http://www.atlantskainicijativa.org/aibos/images/stories/ai/pdf/brosure/Analiza%20sigurnosnih%20rizika.pdf [Accessed 30 April 2014].

Beanland, Christopher. 2013. The pride of Sarajevo: How football is uniting a once bitterly divided nation. The Independent, 26 October. Available: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/the-pride-of-sarajevo-how-football-is-uniting-a-once-bitterly-divided-nation-8899773.html (Accessed 15 May 2014).

Bieber, F. (2006) Post-War Bosnia: Ethnicity, Inequality and Public Sector Governance, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Billig, M. (1995) Banal Nationalism, London: Sage.

Dedović, Edin. 2013. The Bosnian national football team: a case study in post-conflict institution building. Open Democracy, 14 October. Available: http://www.opendemocracy.net/can-europe-make-it/edin-dedovic/bosnian-national-football-team-case-study-in-post-conflict-instituti (Accessed 15 May 2014).

Edensor, T. (2002) National Identity, Popular Culture and Everyday Life, Oxford: Berg.

European Commission. 2013. Bosnia and Herzegovina 2013 Progress Report, 16 October. Available: http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/pdf/key_documents/2013/package/brochures/ bosnia_and_herzegovina_2013.pdf (Accessed 6 May 2014).

Fadilpasić, S. 2013. Crazy celebrations in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Al Jazeera, 16 October. Available: http://blogs.aljazeera.com/blog/europe/crazy-celebrations-bosnia-and-herzegovina (Accessed 7 May 2014).

FIFA. 2013. FIFA Statues, July 2013 Edition. Available: http://www.fifa.com/mm/document/AFFederation/Generic/02/14/97/88/FIFAStatuten2013_E_Neutral.pdf (Accessed 18 May 2014).

FIFA. (2014a) FIFA World Cup. Available: http://www.fifa.com/aboutfifa/worldcup/ (Accessed 17 May 2014).

FIFA. (2014b) FIFA accociations. Available: http://www.fifa.com/aboutfifa/organisation/associations.html (Accessed 18 May 2014).

FIFA. (2014c) Croatia: Profile. Available: http://www.fifa.com/worldcup/teams/team=43938/profile-detail.html (Accessed 18 May 2014).

Gasser, P. K. and Levinsen, A. (2010) “Breaking Post-War Ice: Open Fun Football Schools in Bosnia and Herzegovina”, Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics [online] 7 (3), pp.457-472. Available: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1743043042000291730> [Accessed 8th November 2013].

Hobshawm, E.J. (1992) Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hopkins, V. (2014) “We are hungry in three languages”: citizens protest in Bosnia, Open Democracy, 13 February. Available: http://www.opendemocracy.net/5050/valerie-hopkins/we-are-hungry-in-three-languages-citizens-protest-in-bosnia (Accessed 17 May 2014).

Horne, J. and Manzenreiter, W. (Eds.) (2006) Sports mega-events: social scientific analyses of a global phenomenon, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Kinder, Toby. 2013. Bosnia, the bridge, and the ball. Soccer & Society 14 (2): 154‒66. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2013.776465 (Accessed 15 January 2014).

Lincoln, Allison in Terry Monnington. 2002. Sport, Prestige and International Relations. Government and Opposition 37 (1): 106–34. Dostopno prek: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1477-7053.00089/abstract (8. november 2012).

Mahmutčehajić, R. (1999) “The War Against Bosnia-Herzegovina”, East European Quarterly 33 (2), pp.219-32.

Nauright, J. (2010) Long Run to Freedom: Sport, Cultures and Identities in South Africa, Morgantown: Fitness Information Technology.

Niemann, A., García, B. and Grant, W. (Eds) (2011) The transformation of European football: Towards the Europeanisation of the national game, Manchester: Manhester University Press.

Nogometni/Fudbalski savez Bosne I Hercegovine ‒ NFSBiH. 2014. Istorija. Available: http://www.nfsbih.ba/bih/tekst.php?id=7 (Accessed 14 May 2014).

Press Online Republika Srpska – Press RS. 2013. BiH na svetskom prvenstvu u Brazilu, 15 October. Available: http://pressrs.ba/sr/video/video_vesti/story/46889/(VIDEO)+BiH+na+svetskom+prvenstvu+u+Brazilu.html (Accessed 10 May 2014).

Smith, A. (1998) Nationalism and Modernism, London: Routledge.

Smith, A. and Porter, D. (Eds.) (2004) Sport and National Identity in the Post-War World, Oxon: Routledge.

Sportal.rs. 2014. Slavje u Federaciji BiH: Zenica, Mostar, Bugojno i Incko pozdravljaju Džeka I družinu, 16 October. Available: http://www.sportal.rs/news.php?news=111568&com_page=1#comments_box (Accessed 16 May 2014).

Sport.ba. 2014. Više Bošnjaka u Borcu nego u Sarajevu, u Širokom samo Hrvati i Brazilci, 3 April. Available: http://www.sport.ba/fudbal/vise-bosnjaka-u-borcu-nego-u-fk-sarajevo-u-sirokom-samo-hrvati-brazilci/ (Accessed 7 May 2014).

Sterchele, D. (2007) “The Limits of Inter-religious Dialogue and the Form of Football Rituals: The Case of Bosnia-Herzegovina”, Social Compass [online] 54 (2), pp.211-224. Available: http://scp.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/54/2/211 (Accessed 7 December 2009).

Sterchele. D. (2013) “Fertile land or mined field? Peace-building and ethnic tensions in post-war Bosnian football”, Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics [online] 16 (8), pp.973-992. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.801223 [Accessed 15th January 2014].

Sugden, J. and Tomlinson, A. 1998. FIFA and the contest for world football: Who rules the peoples’ game?, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Sugden, J. (2010) “Critical left realism and sport interventions in divided societies”, International Review for the Sociology of Sport [online] 45 (3), pp.258‒272. Available: http://irs.sagepub.com/content/45/3/258 [Accessed 16 April 2014].

SuperSport. 2013. Bosnia’s qualification highlights ethnic split, 16 October. Available: http://www.supersport.com/football/world-cup-2014/news/131016/Bosnias_qalification_highlights_ethnic_split (Accessed 15 May 2014).

Tomlinson, A. and Young, C. (2006) “Culture, Politics, and Spectacle in the Global Sports Event – An Introduction”, in Tomlinson, A. and Young, C. (Eds.), National Identity and Global Sports Events: Culture, Politics, and Spectacle in the Olympics and the Football World Cup, New York: State University of New York Press.

Topalbećirević, Sabahudin. 2014. Reprezentacija BiH, igrači, navijači, mediji. Brze Vijesti, 6 March. Available: http://www.brzevijesti.ba/clanak/7624/reprezentacija-bih-igraci-navijaci-mediji (Accessed 17 May 2014).

Van Koningsbruggen, P. (1997). Trinidad carnival—a quest for national identity. London: Macmillan Education.

Wilson, Jonathan. 2014. Despite its inescapable past, Bosnia-Herzegovina writes new chapter. Sports Illustrated, 28 April. Available: http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/soccer/news/20140501/bosnia-herzegovina-world-cup-dzeko-yugoslavia/index.html (Accessed 9 May 2014).

Wilson, P. (2014) Asmir Begović: I am proud to play for Bosnia, country has been through a lot, The Guardian, 15 May. Available: http://www.theguardian.com/football/2014/may/15/asmir-begovic-bosnia-stoke-world-cup-2014-brazil (Accessed 16 May 2014).

Witzig, R. (2006) The Global Art of Soccer, New Orleans: CusiBoy Publishing.